All I ever wanted was to sing to God. He gave me that longing... and then made me mute. Why? Tell me that. If He didn't want me to praise Him with music, why implant the desire? Like a lust in my body! And then deny me the talent?

-- Antonio Salieri in Peter Shaffer’s “Amadeus”

Sometimes when I first meet new people, they guess I’m a musician. Between my long hair and bohemian style of dress, I know it’s a reasonable assumption, but I like to think that they’re picking up on an intangible. I am a musician, though not in the way that most folks might expect. I don’t play smoky honky tonks, and I’ve never ridden on a tour bus, but I do play and compose music. Very few people have heard anything I’ve ever written -- though there was that one time when one my songs ended up in a computer game score (blog posts about that coming later.) And in 2022, the world will hear “The Mare of Farewell,” my first-ever released single. But the road to getting to it has been anything but short and easy.

For most of my life, music has been as integral to who, as much so as are writing and my filmmaking. But it’s not something I’ve been confident enough to share with many people, though that’s begun to change over the past few years. Beginning with the revival of my Uncharted Regions audio drama series in late 2017, I found the courage to use my compositions to support the musical needs of my audio and film projects. I’ve even opened myself up to the possibility to create for other producers. It’s a place I’d never expected to reach. It’s fun and it’s exciting, and I’m looking forward to where this goes, but looking back I have to take stock of how I got here. It was anything but inevitable, and there were several points at which I nearly gave all of it up.

On a Saturday long ago, I’m playing in a forest of audio cables. They radiate outwards in every direction, looping like vines over a buzzing mass of amps, mics, drums, guitars, effect pedals, and instrument cases. There are so many knobs that cry out to be fiddled with, to be turned...but I’ve been given strict orders to touch nothing. It’s a hard command to follow. Everything here attracts me, from the overheated vintage amplifiers that smell like lightning and hot coffee to the stacks of gleaming guitars begging to be strummed. I’m perplexed because all of this stuff is in my living room, materialized on the spot for an afternoon rehearsal by my brother’s band. How can I not play with something that’s in my own house?

In truth, my desire to mess with everything is about more than the gear. This is also about my wanting to be connected, not just to my brother Gene and his bandmates, but also to my father and the rest of my family. For as far back as I can remember, my weekends have been defined by listening to my father and my brother playing their guitars. Tunes by Bob Wills, Hank Snow, Chet Atkins, Conway Twitty, and Roy Clark are all in regular rotation on my father’s chosen playlist. “Under the Double Eagle” is trotted out so frequently that it’s practically a family anthem, and it’s the song I most frequently associate with their playing together. On several occasions Gene has tried to expand my father’s repertoire with songs from Led Zeppelin or Frank Zappa, but my father won’t have it. He’s got old-fashioned tastes, and he knows what he likes to play. He was, afterall, playing honkytonks and roadhouses long before Gene came into the picture. Dad’s even got a record that he and his buddies laid down during his gigging days, but he’s happiest just playing for us and for himself.

IN THE BLOOD - A photo of my father, Henry Gene Hallford, taken two years before his death in 1996. Like myself, dad was irresistibly attracted to any musical instrument put in front of him, and enjoyed noodling around on my Ensoniq TS-10 synthesizer.

As much as I’d like to be able to jam with them, I’ve already discovered that their instrument of choice isn’t easy to take up. I’m confounded how the same note on a guitar can be played a half dozen different ways depending on the note played before it. I hate having to build up callouses on my fingers so I can bear to touch the strings. It seems like everything about it has been designed to drive me away.

By comparison, my mother’s favored instrument always made more sense. On a piano everything is laid out in front of you. The notes you see are the ones you play, and no transpositional mental gymnastics are required. The only real catch is that we don’t have one in the house...at least not yet. We do, however, have an ultra-annoying home organ that sounds -- and plays -- exactly like a dying cow. A year previously my parents had bought the beast for me with good intentions, thinking I could take piano lessons from our church choir director. After six exhausting months, her irritable-school-marm teaching style combined with her suffocating curricula of kiddie tunes and church hymns all but obliterated my interest in taking formal music lessons. In the end, I decided that she would not be the one who could help me get to where I wanted to be.

Even without a formal teacher, I’m still obsessed with mucking about with practically anything musical. At my elementary school I bang away on the upright piano in the music room. In malls, I haunt the ever-present organ stores. But more than anything else, it’s an instrument from another age hidden on my grandparents’ farm that holds my imagination more than any other.

Tucked away in a rarely used parlor was a piano. A pair of sliding wooden doors barred the way into the room, and even when opened, the place is almost always cloaked in shadow. It’s only via in a slash of light coming from the doors that you can see the long-neglected hulk sitting in the corner. It’s badly out of tune. Many of the keys have lost their ivory veneers, and some no longer sound when struck because their wires have snapped. But for all the indignities of its advanced age, this piano is unlike anything else I know. This is a piano that can play itself.

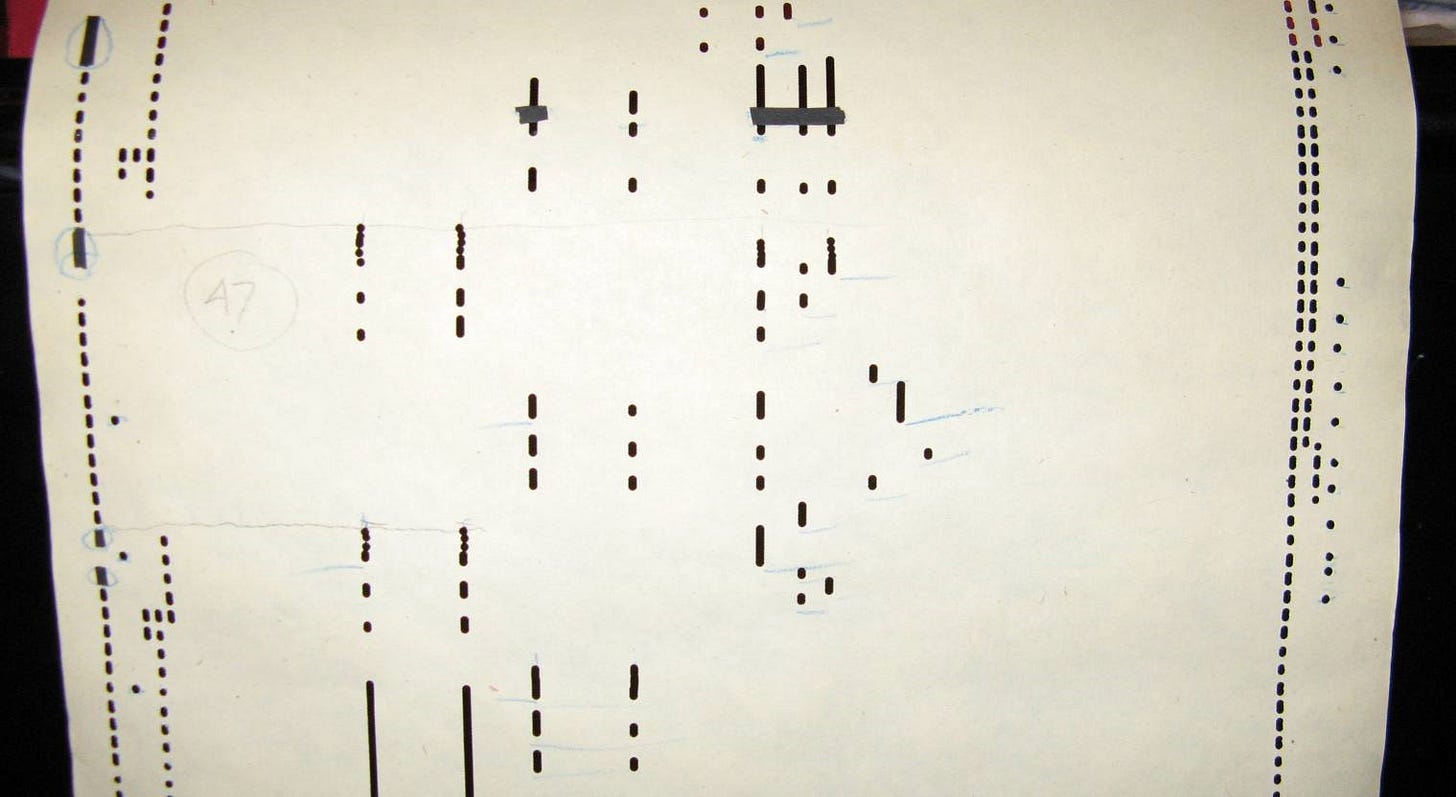

It’s an unusual day when I can actually coax my tiny grandmother into pulling out one of the player rolls. She worries about them disintegrating into dust, but sometimes I can exploit my status as her favorite grandchild and get her to take one out of the closet. When she does, it’s easier to understand her concern. The song rolls are thick, but they grow increasingly yellowed and brittle with every passing year. She insists on loading up the player spindle herself to minimize any chance of damage, but once she’s done, she backs away so that I can do the fun part of working the foot bellows. I pump, pump, pump and the cylinder spins. The piano keys begin to dance as if touched by a ghostly hand, and I’m always delighted as the instrument jangles out a tune as if by magic.

Before the player rolls are returned to their places, I’m always inspired by their simple ingenuity. Each one of them is just a long strip of paper drilled through with a pattern of holes. Each hole’s position determines what note will be struck, and the length of each hole determines how long the note will sound. With just these two bits of information, the piano is capable of spinning out any number of waltzes, operas, ballads, or any other musical genre that can be rendered by piano. In the future, this metaphor will play a critical role in my understanding of musical composition.

FAMILY HEIRLOOM - My younger cousin, Jimmy Swanson, sits at the keyboard of the player piano as it existed in my grandmother’s “parlor.”

LET IT ROLL - An example of a player piano (also called a pianola) piano roll. My grandmother had dozens of these in a special cupboard and carefully guarded them. Unfortunately, the rolls and the piano were burnt to ash when an arsonist destroyed our family farmhouse in 2017.

At the start of fifth grade, I’m excited because this is the year we’re allowed to sign up for school band. I’ve been thinking all summer about what I want to play. Guitar and piano are off the list because this is explicitly marching band, so I’m having to consider other options. Xylophones are at least piano-like, but they look so dorky that I’d never want to get caught playing one in public. Trumpets are cool, as are trombones, but my heart is gravitating towards something new...the saxophone. I like the sound of them, and even in elementary school I’m hearing rumors that girls like sax players. (Theoretically they’re better kissers for some reason. Maybe it’s from all that mouth puckering.)

While we have a regular music class at my elementary - it’s mainly a music appreciation course - the band class is taught once a week, and the instructor comes down from Charles Page High School to teach it. Along with myself, David Guthridge and Tracie Stone have signed up, both neighbor kids from my street. David and I have been best friends practically since birth, and Tracie’s a cute, shy girl who’s only recently moved in next door to me. Also joining are Jodee Tubby, Pam Smith, and Jenaan Suleiman. We’re already a tight crew because of our freakishly small class - only about ten of us in my grade - so it’s nice that we’re already friends and used to being around each other a lot.

When Mr. Osborne arrives, we’re all in the music room, and he quickly spells out the way things are going to be. The point of this exercise will be to learn not only how to play music, but to play it as part of an ensemble. We aren’t, afterall, just a collection of soloists playing in the same room (though it will sound that way for a while.) We’ll also be learning how we can play and march at the same time so that we can join other kids in a district-wide band that will play in the city Christmas Parade.

Everything’s going smoothly as Osborn begins to approve our instrument choices. The girls seem happy to divvy up flutes and clarinets between them while David picks the trombone. Before we can discuss my choice of saxophone, however, Mr. Osborn brings up a concern. There’s a major problem in our nascent band. We are meant to march. Marchers need a beat. A beat requires a percussionist, but no one has so far volunteered to fill that hole. Would I be willing to consider playing snare?

I can feel everyone else looking at me. There’s a clear implication from the director that we can’t be a band without a drummer. Am I allowed to say no? Am I out of the band if I refuse? I’m almost a whole year younger than everyone in my class, so I’m used to just going along with what everyone else says. It’s complicated by the fact that I was also raised by a mother with authority issues so I’m not great at speaking up for myself or for what I want. Maybe Osborn’s being kind. They’ve already told him that I’m asthmatic so maybe he’s thinking I won’t have the lungs to play one of the other instruments. All those eyes are on me, waiting for an answer. But I want to play sax, I want to play sax, I want to play sax...

“Okay,” I say, surrendering without a fight. “I’ll play snare.”

A little part inside me dies. I’ve lost another shot at learning how to play something melodic in favor of just backing up other people, but I figure it’s my price for belonging. For the duration of this first meeting with Osborn I’ve got the lyrics to Little Drummer Boy running through my head. “I have no gift for you but my rum pa pum pum, rum pa pum pum, rum pa pum pum.”

LITTLE DRUMMER BOY - Our fifth-grade band assembles prior to a parade in Sand Springs, Oklahoma. The players from left to right. Front Row: Tracie Stone, Pam Smith. Back Row: Me, Jenaan Suleiman, Jodee Tubby, and David Guthridge. (Photo courtesy of David Guthridge)

The following year, as we are preparing for another parade, Osborn takes me aside once again, this time to let me know that they’ve got a surplus of snare players for the parade. They need someone to play the bass drum. I can tell by the way he’s sizing me up that this isn’t principally about my drum-playing. This is about my size. He sees a fat kid with broad shoulders. He’s thinking I’ve got the build and the legs to carry around a big bass drum. Wouldn’t that be fun to be the person leading the beat for everyone in the band?

I still don’t know that I have the right to say no. Over the past year I’ve learned to enjoy playing the snare, but it’s not the limitations of this new instrument that worry me now so much as the bulk of it. Between my weight and my asthma, it’s already an effort for me to handle marching while playing the snare. But to consider taking on an instrument that I could have curled up inside of...it gave me pause. Osborn assured me everything would be good, that I’d be fine. Once again, against my better instincts, I fall on my sword for the greater good of my bandmates.

On the day of the Christmas parade we convene in a parking lot. The lot’s full, and our contingent from Twin Cities seems so tiny compared to those who are coming from other elementary schools. It’s a little intimidating to be surrounded by so many unfamiliar faces, but there’s also an instant comradery with all these strangers who are there to do the same thing as we are. Within a few minutes instruments are coming out of their cases all around me, a cloud of experimental honks, squeals, trills, and other sounds rising in a cloud as everyone starts warming up.

For me, I’m staring at the bass drum case sitting on the lowered tailgate of our station wagon. It’s a big, black, round box that’s large enough to bury an adult St. Bernard. It’s a huge effort to even get the lid off the thing. Once it’s out of the case, I let the tailgate support the weight of it while I clip it on to my harness. I arch my back slowly to lift it off the tailgate and I swing it around, remembering how to keep my balance with it. I’ve had a little practice with it marching around the streets near my elementary school, but I’m still not at all used to it.

Within a few minutes there’s a whistle from Osborn, and the band lines up, slipping into position on the parade route behind the floats but in front of the horses. Everyone is excited to get started, but I’m already beginning to feel the weight of the drum. Worse, it’s unseasonably warm today, and heat and I do not play well together. It isn’t an auspicious omen. When at last we get the triple whistle to kick off, I’ve already got a bad feeling about how things are going to go.

The parade route is adorned with all the magical finery of Christmas. There are oversized snowflakes, and red bows, and electric lights strung between light poles. Because this is a more innocent time before the distractions of the internet or computer games, crowds pack both sides of the street, hooting and clapping as our elementary school band marches by. I have to assume it’s a spectacular view, but my perspective is limited. My eyes are just below the top curvature of the drum, so all I can catch is what’s in my periphery. It’s like the opposite of being a horse with blinders. I can see everything except what’s in front of me. To me the whole world is just my drum and the beat I’m laying down.

BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM.

Five blocks in I’m already sweating like a pig. My eyes burn from the salt river that’s pouring down my forehead, but I can’t afford to break the beat to mop my brow.

Keep the beat, just keep the beat. Everyone is counting on you.

I’ve got to keep time, keep the cadence. I’m also doing my best to make sure that I’m in step...at least with everyone I can see.

Got to keep everyone moving.

BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM!

I don’t need to be able to see in order to play, but my growing inability to breathe is warning me that greater trouble is on the way. I’m sucking in air as fast as I can, and I can tell that the other drummers in my line are looking at me and whispering to each other. None of them know me, but I gasp that I’m fine, I’ll be okay.

Keep moving.

BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM.

Can’t stop. Can’t stop. Everyone is counting on me.

By the last quarter mile of the route, my march has devolved into a drunken weave. My breath is ragged and hard, and I’m surprised that anyone can hear the rest of the band over my wheezing. I’m plodding ahead, doing my best not to pass out.

BOOM. BO..BOOM. B...

Suddenly Mr. Osborn is alongside me. I can tell from his hawk-like expression that he’s come to scold me about by my increasingly erratic playing -- but he gets a good look at me and it’s clear he thinks better of it. For the remainder of the route he stays near my side.

As we reach the end of the route and the band falls out, I stagger away from everyone, making a beeline to a concrete island filled with grass out front of a bank. My legs give out from under me, and I collapse face up, staring into the sky, the drum flopping to the side as I go down. The world is spinning, and my wheeze has become a full force roar in my throat. From the pounding in my chest, I can almost imagine that I’m still playing the drum —

BOOM, BOOM, BOOM

— but it’s my heart slamming against my ribs, trying to keep me alive even though there’s not enough oxygen in my system. Through a burning haze of sweat, I see my mother and Mr. Osborn rush over to me, both of them chattering about how pale I look. All I can think about is my throat closing up, and how I don’t want to die in a Christmas parade in front of all these strange kids I don’t even know. I’m horrified that this is going to be their first impression of me, that they’re all going to remember me this way, but there’s absolutely nothing I can do about it.

For the next three days, I’ll be confined to my bed with one of the worst asthma attacks of my life.