The Long And Winding Road, Part II

By the close of my junior year in high school, I’ve got an important decision to make. I’m going over the enrollment form for my final year, and I’ve ticked all the boxes for my general education requirements, but I still need to pick my electives. Journalism is an automatic choice because I love the program, and I’ve already been promised the editorship of the school magazine for my senior year. More than that, the advisor of the program is like a second mother to me. On several occasions Mrs. Schaub has gone out of her way to encourage my writing, and to see that I submit for the monthly statewide journalism awards. My second elective choice is a little harder to make. For every year since elementary school, I’ve had band as an elective, and I’ve never had any hesitation in ticking the box for it. This year, though, I’m wondering if it’s worth it.

In junior high I’d learned all the essentials of being part of a marching band. I’d learned how to keep in step, to play with others, and to have the discipline to practice even when I wasn’t always enjoying myself. I’d learned how to take criticism about what I was doing, and how to be responsive to feedback. All of it had been helpful and informative, but along the way I’d also made a disheartening discovery about myself. As a performer, I was middling at best. My hands would cramp badly if I held the sticks for more than a few minutes at a time. Hours and hours of practice failed to improve my co-ordination, and sometimes my hands would begin to shake so badly that it was an effort to even stay on beat. Bandmates sometimes accused me of not caring, or not applying myself hard enough, but none of them knew the struggles I was enduring to be able to play at all. I found myself torn between my ambitions and my reality, but ultimately had to make peace with my limits. I might never become a rock-star player, but I knew I could be good enough to satisfy an audience.

When the time came at last to graduate from junior high, I was anxious to move up. Charles Page High School had one of the most award-winning bands in the state, and I was looking forward to taking the field with them. CPHS Band Director Gene Osborn had previously come down to the junior high several times to scout our concerts for who he wanted, and he’d been impressed with how well I’d handled playing tympani in the Central Junior High orchestra. Naturally, he figured I’d be a great prospect to play tri-toms in the high school drum line.

DRUM LINE - Pictured here with my CPHS “Gold Pride of Proud Country” drum line in 1981, during my sophomore year in high school. It’s the only band photo that I’m in that’s sharp enough for me to recognized clearly. You can spot me (and my fro) on the second from the right. Also pictured here, third from the left, is snare player Matt Harris.

I was too young at the time to have seen what was coming. I hadn’t been wise enough to add up all the hints I’d had over the years about the man I was volunteering to go play for. In elementary school, Mr. Osborn had seemed like a stern but patient teacher who genuinely wanted to help me learn music. But once I pierced the veil, once I was in the promised land of his band room that I’d been dreaming of for five years...I discovered that Oz the Magnificent had been nothing but a smokescreen. At the high school, he ran his program like a despotic dictator. He threw music stands at teenagers when he thought they weren’t listening to him. He screamed into the sobbing faces of students when they failed to meet his expectations. One year, after we’d returned from a state band competition with a first-place win in our division, Osborn smashed our hard-won trophy against the floor because we’d failed to win the sweepstakes prize. For a quarter of an hour he railed at us about how worthless we were, and how he’d never accept a mere 1st place win from us ever again. He controlled us with fear and intimidation, and frequently pointed out that his name and his title -- Gene Osborn, Director -- spelled out G.O.D.. It was clear that he didn’t think of us as his students, or even as human beings. We were his sniveling, inadequate troglodytes, and he was our rightfully angry deity.

If I’d been almost any other student, I might have avoided most of G.O.D.’s wrath. I paid attention whenever he was in front of the band. I showed up on time, did my work, and tried my best. Nevertheless, I was always at a disadvantage with him. For years he and my father had been locked in a private war. Because my father was an auxiliary police officer (in addition to being the head of all vocational programs in Sand Springs), my dad had control over most of the security at the high school. Mr. Osborn would rage against my father regarding access to the band room, where buses could park, over any possible thing he could find fault with. Each time they got into a new squabble, Mr. Osborn would come up with a new and creative way to make me pay for my father’s policies.

ONE ADAM HALLFORD - This is my father as most of the teachers and students at Charles Page High School would have usually known him, seated behind his desk in the so-called “red hall.” He was the first vocational director for the Sand Springs school system, a vice-principal, and also, because he was an auxiliary police officer for the Sand Springs Police Department, served as the high school public safety officer. It was dad’s latter role that would cause so much friction between he and Mr. Osborn, and this in turn this would make me a target for special mental abuse at the hands of the high school band director.

I was barraged constantly with non-musical tirades: my hair was too long, I weighed too much, he didn’t like my clothes, my hobbies were stupid. By the end of my junior year, Osborn’s critiques of me were an almost a daily affair, and he was hinting darkly that he was going to demote me to playing cymbals. I was to be his compliant percussion monkey, and he’d do with me anything that he wished.

Even with all this personal abuse taken into account, I struggled with the decision about whether I’d stay in band or not. It wasn’t just about leaving behind the music. Osborn enforced an infantile, draconian rule that once you left the band you were to be ostracized publicly by your peers as a “band quitter.” He forbade band quitters to enter the band room, to be near the band shell during football games, and he’d even forbid band members from being seen fraternizing with band quitters. If I walked away, there was a strong chance I’d lose several of my closest friends...and yet, I could no longer find a compelling reason to continue enduring the charade. I wasn’t interested in band as a blood sport. I’d signed up to learn how to play music, not to be a pawn in his capricious power trip.

In the end, I decide at last that it was time for me to move on, and I checked a new box on the electives form. I was determined to find another way to make music on my own.

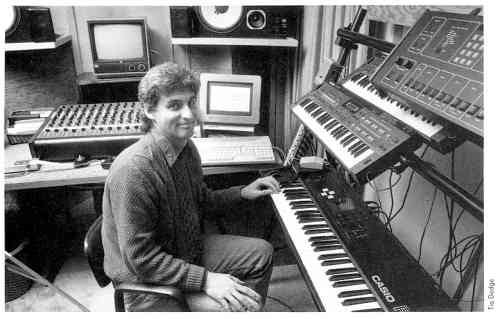

Two years later I’m in a makeshift recording studio that used to be a Christian Science Reading Room. I’m perched quietly on a drum stool and doing my best not to distract my buddy. Likely my caution isn’t even necessary, but I’m doing my best to be respectful of his space. He’s deep, deep into his zone, fluidly running through guitar licks as he looks for exactly the right hook. After a few minutes he finally lands on something, and his face lights up with a boyish grin. Yeah, yeah, yeah. That’s it. He loops through it a few times more for practice, then stomps a pedal connected to his recording deck. Immediately it thunders to life like a hot rod, the yellow, backlit VU meters bouncing while an infectious groove bleeds out of his headphones. Even before the punch-in arrives for the track he’s laying down, his fingers are flying over a riff that would make Eddie Van Halen sweat. But for Matt it all seems effortless, like he’s been doing this his entire life. He’s alive and laughing and radiating energy the whole time, a blonde-maned, rock ‘n roll Krishna at play in ripped up jeans and a white t-shirt. Joy in each and every note. I’m in the presence of something I’ve been looking for nearly my entire life.

Before I’m ready for it, the music stops. I’m still bopping my head to a phantom beat when I see that his nose is wrinkled up and he’s staring at me. “WHAT DO YOU THINK?!” He yells his question again, not thinking about his headphones or how thunderous it sounds in the otherwise empty room.

He’s being generous. He doesn’t need my advice or my input. In a few short years he’ll be writing and performing songs with music legends like fellow Tulsan Leon Russell. He'll even write songs with Bernie Taupin (best known for being the lyrics man for Elton John). Matt’s musical gifts are far and away much greater than any I possess, or ever will, so any feedback I have to offer is rhetorical at best. I’m just honored that he lets me into his playground while he works.

“Sounded good to me,” I tell him.

“Naw, I fucked up. You probably couldn’t hear it.”

He slips off his headphones and thrusts them at me. Dutifully I slip them on as he winds back the tape on his Tascam 388, a high-pitched warble sounding in my ear. At last he finds the section he wants to review and he hits play, his head leaning in near mine as he listens with me.

“D’ja hear that?” He blows a raspberry, giving a critique of his performance. Even so, he doesn’t seem particularly upset about the screw up. Even with the headphones on, the sour note is barely even noticeable to me, but now I won’t be able to ignore it.

“It’s not that bad,” I tell him.

“I can fix it.”

As he gets to work, he has no idea what he’s done today. For him, he’s just crafting his demo with a friend there to provide moral support. For me, though, it’s like he’s switched on a light in a darkened room. Maybe being a musician doesn’t have to be about always being perfect. Maybe it doesn’t have to be about playing in front of an audience. Maybe I can compose and record rather than trying to become the virtuoso player I’ve realized I’ll never be. I’ve had my first real taste of the power of the multitrack recorder.

REELING IN THE YEARS - Matt Harris’ Tascam 388 was the first dedicated 8-track recorder / mixer combo I ever laid eyes upon. After its release in 1985, the Studio 8 deck became the go-to workhorse for many indie recording artists, and was much beloved for its warm, lo-fi sound.

Not long after my time in Matt’s private studio, I’ve begun my own experimentation with music production - though the tools I begin with are not exactly professional. I’m armed with a positively stylin’ navy-blue, portable Yamaha Portasound PS-400 that can rock your socks off...providing you enjoy vaguely-string section-sounding licks set to a bossa nova beat. If that doesn’t immediately set your toes to tappin’ I can switch to a surprisingly good organ, a tinny piano, a section of sickly trumpets, or something that might be construed as a guitar (if you’ve never heard a guitar before.) It goes everywhere I go in the backseat of my car, and if I have time alone, I whip it out for practice.

My recording gear is slightly more sophisticated. I’ve picked up a Fostex X-15 - a 4-track cassette recorder - that I’ve purchased from my buddy and frequent partner-in-crime, Ron Bolinger. The recorder has a few distinct advantages, the first of which is portability. I can take it anywhere so I can record at any time and in any place that suits my fancy. Like the Portasound, it goes with me everywhere so that I can lay down an idea at the lake, or in the woods, or anyplace an idea might unexpectedly present itself. A second advantage is that it runs on D-cell batteries and uses standard cassette tapes, meaning that I can run down to the nearest convenience store if I need more juice or blank recording media. I have, in essence, the first truly important tool in my composer’s toolbox, a kind of audio “sketchbook.”

KEYED UP - My first portable keyboard, the Yamaha Portasound PS-400. More of a toy than a real instrument, but it became the first thing I could take virtually everywhere and play.

GETTING IT DOWN - The Fostex X-15 operated exactly like a standard cassette recorder except that signals could be tracked independently to each channel, allowing up to four different mono tracks to be mixed together. Two tracks could also be “bounced” together to a third track, allowing a theoretically infinite number of tracks to be laid down, but this came at the cost of a degradation in sound quality.

Between the Casio and the Fostex, I compose several tunes including my Frank Zappa-esque magnum opus, “Custard Sandwich,” (featuring my own vocals) but I’m not exactly attaining my goals of making music that anyone else would want to listen to. I’ve taught myself how to play, to compose, and to record, but by the time I’m in junior college, I’m itching to get my hands on a real instrument...but it can’t be just one, can it? If I wanted to be a one-man band, how could I afford to buy all those instruments, and how could I find the time to learn all those fiddly articulations and techniques and skills? But the truth was, I didn’t need a dozen different instruments. I could buy just one instrument and could have any sound I could imagine instantly available at my fingertips. I was living smack dab in the middle of the 1980s during a revolution in music production, brought about largely by the golden age of the synthesizer.

For anyone else, the leap to synthesizers would have seemed like a no-brainer, but for me, I had to do a bit of mental de-programming. Most of my musical tastes had been shaped by my nine-year-older, guitar-playing brother. Despite the already omnipresent status of the synthesizer in rock music during the 1970s, Gene quite vocally detested the instrument, and did his best to instill the same opinion in me. I was allowed to enjoy The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, Led Zeppelin, Bachman Turner Overdrive, Three Dog Night, Don McClean, Jim Croce, and generally any band that had released an album before 1975. (Paradoxically, Emerson Lake & Powell were allowed, and for reasons that continue to elude me, he had a Yes 8-track in his car case, though I have no memories of it ever actually being played.) Progressive rock was anathema, and while he enjoyed classical music, he disliked anyone attempting to do something that was classical-like with anything other than a living, breathing orchestra. And so, for most of my teenage years, I was hopelessly out of touch with my classmates, and had to do my best not to like any of the new-wave music featuring those abhorrent synthesizers.

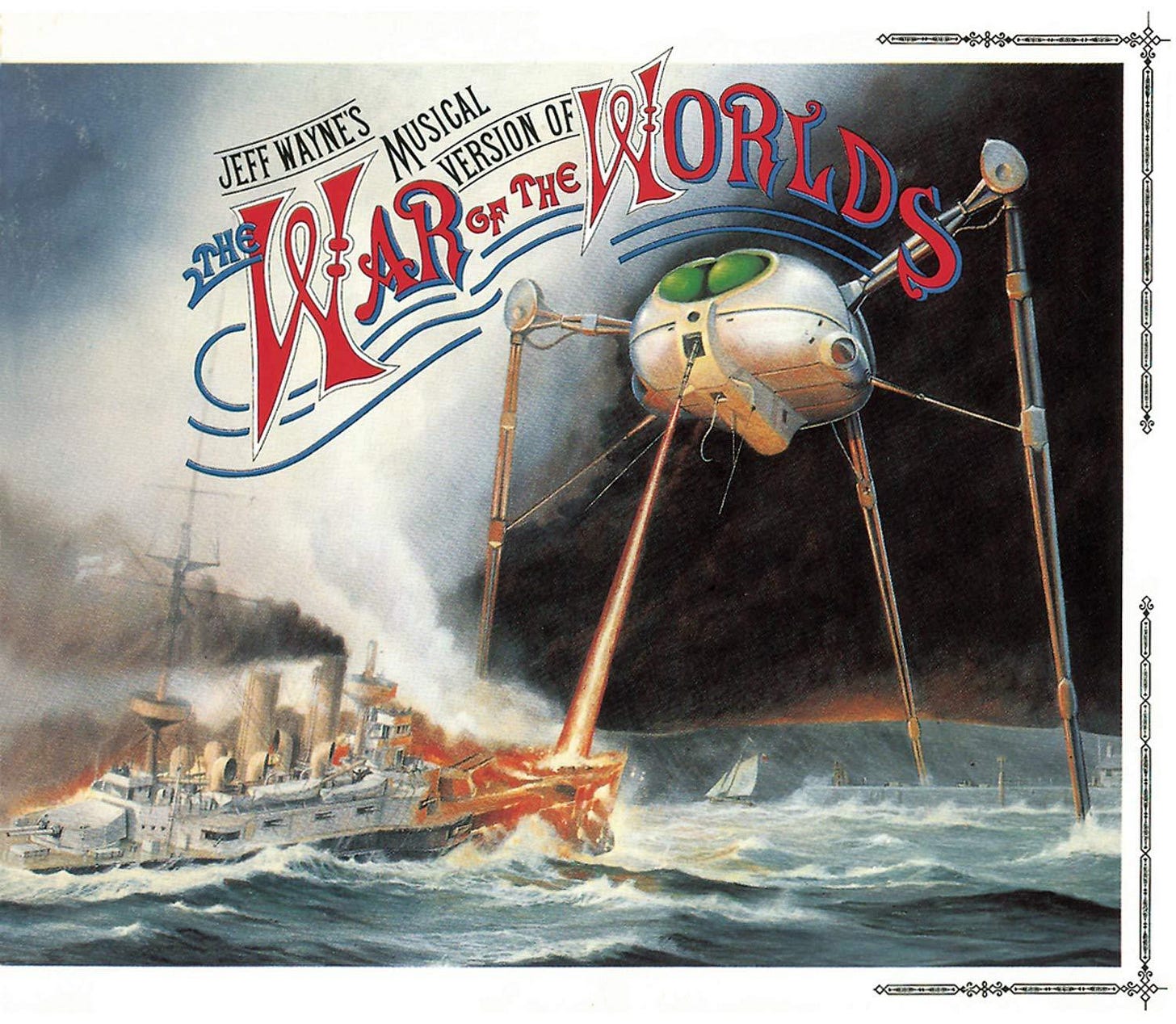

Despite Gene’s best efforts, however, he had made one critical error in letting one particular album past my music filters, an album which was both a rock album, and also a science-fiction opera. It was at its core the most prog rock album of its era, and something which simply could not have existed without the presence of stacks and stacks of synthesizers. It was allowed, presumably, because it was essentially an audio-drama based on one of the best-selling science fiction stories of all time and starred the incomparable Richard Burton. Not only was it one of the best albums to have come out of the 1970s, but it also featured the amazing cover and interior artwork of Roger Dean, best known for being the cover artist for practically every major album produced by Yes. I am talking, of course, about Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds.

OOOOHLAHHHH - Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds is quite arguably the best rock opera ever made, and has since been adapted as a stage play, a computer game, an animated movie, and even an interactive theater VR experience which I visited in London in 2019. It remains one of my all-time favorite albums of any kind.

And so, the Martians broke through the line, and they brought their glorious synthesizers ooohlahhing along with them. My aversion became a deep and abiding love. I branched out to embrace other prog rock bands, as well as new-wave artists like Depeche Mode, Erasure, and Information Society. Discovering the soundtrack work of Tangerine Dream and Vangelis and Kitaro lead me to electronic musicians who crossed multiple genres like the man who became my new musical hero, Jean-Michel Jarre. I was in, and I was in deep.

Fortunately for me, it isn’t difficult to get information on the equipment that these artists are using to create music. The newstands of the 1980s are brimming with magazines that feature write-ups not only on the recording artists, but on in-depth reviews of their gear. I devour every issue of Keyboard magazine and Electronic Musician as soon as they arrive, pour over every stage photo to get an idea of what the pros are all using. There are brand names that come up repeatedly: Moog, Sequential Circuits, Oberheim, Roland, Yamaha, Korg, Kurzweil. They’re like the names of saints to me. The amount of available stuff out there is jaw-dropping, but I’m looking for the silver bullet, the one synthesizer that seems to be the one that everyone is using. It doesn’t seem to take very long to find the darling of the moment: the Yamaha DX-7.

Another name which begins to turn up is one that I don’t expect to see, at least not in this context. It’s the name of a computer which many musicians are using because it comes with built-in MIDI ports, a communications protocol which allows synthesizers and computers to interoperate. It’s the only computer brand which comes wired - straight from the factory - ready to hook together to an electronic instrument. It’s a brand that I’m loyal to because it’s the same brand as my first home computer, the same brand as the first home gaming system that most Americans had ever touched. It is THE most 1980s brand of the 1980s - ATARI - and along with the Yamaha DX7, it would finally put me firmly on the road to composing and recording my own music.

THE KING OF DIGITAL - The Yamaha DX7 became the king of the ‘digital’ synths in the 1980s, known for it’s clean, bell-like tones, ease of programmability, and its famous electronic piano and bass patches. It remains one of the most revered keyboards in electronic music history.

BUILT FOR MUSIC - While the Commodore Amiga became beloved by many visual artists, the Atari 520 ST became the computer of choice for many major recording artists during the 1980s because of it’s built in MIDI ports.